Lincoln Cathedral’s Queen?

Well, no, not really. Eleanor’s association with Lincoln is one of mere happenstance. She is regarded as Lincoln Cathedral’s queen, because of her being interred, at least in part (her viscera, minus the heart), in a tomb within the cathedral following her death in 1290. The story of the procession conveying her body from Lincoln to Westminster, an act of supreme devotion by her husband Edward I, is the stuff of legend to which we shall return later.

Who was Eleanor?

The wife and queen of probably the most successful of all medieval kings, her reputation has fluctuated between being feted and derided, and at times forgotten altogether. She had large independent wealth and landholdings, and apparently a quick temper! An entry in the St. Albans Chronicle of 1308 records that she “was tearfully mourned by not a few… she was a pillar of all England, by sex a woman, but in spirit and virtue more like a man.”

She is far less well known than her famous great-great-grandmother Eleanor of Aquitaine, yet she shared so many of her attributes; she was literate, well educated, an astute businesswoman and a patron of literature and the arts. In fact, she was everything that made her the antithesis of the usual medieval queen. Her marriage was unusual as it is believed that Edward remained faithful to Eleanor in a period when it was almost expected that the monarch would take mistresses. Also unusually, they spent most of their time together, including Eleanor accompanying Edward on his military campaigns.

Marriage to Edward

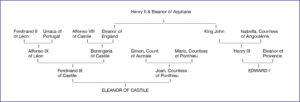

Born in 1241 at Burgos in the province of Castile (a region in what is now northern and central Spain), Eleanor was the last child from the marriage of Ferdinand III of Castile and Joan, Countess of Ponthieu. In her early years she received an extensive education as the courts of both her father, and her half-brother Alfonso X of Castile, were well known for their cultural and intellectual prowess.

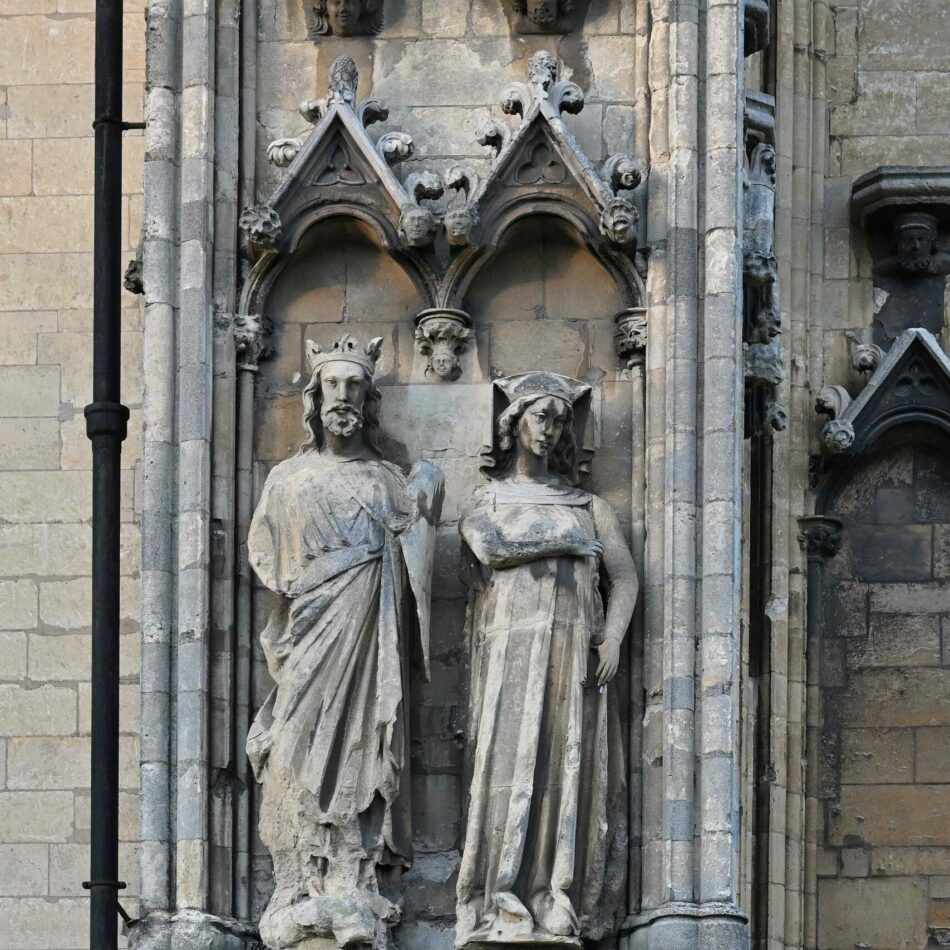

In 1253, negotiations between Edward’s father Henry III and Alfonso X over the future of Gascony resulted in the agreed marriage between Edward and Eleanor. The marriage took place on 1st November 1254 when Eleanor had just turned 13. The newlyweds were in fact related to each other; they were second cousins once removed as Edward’s grandfather (King John) and Eleanor’s great grandmother Eleanor of England were the son and daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine (yes, that is a lot of Eleanors).

Following the marriage the couple travelled to Gascony where they set up their own household, not returning to England until 1255. It was during this time that, it is believed, Eleanor gave birth to her first child, a stillborn girl. Eleanor was to go on to have another (probably) fifteen children, many of whom failed to reach adulthood.

Crusades, childbirth and coronations

Little detail is available of Eleanor’s life during her first few years in England. She was, however, known for supporting her husband in several conflicts, especially the Second Barons War (1264-1267) between Henry III and the barons led by Simon de Montfort. During this time and in the few years preceding her next military excursion with Edward, Eleanor had a further five children with only one surviving beyond six years of age, a daughter named Eleanor (yet another one!) who lived to be 29 years old.

In 1270 Eleanor embarked with her husband on what is now known as the Ninth Crusade. They arrived in Acre, a city at the centre of the kingdom of Jerusalem, to find it under siege. By May 1272 a truce between the factions had been agreed, but in the following month Edward was the victim of an assassination attempt when he was was struck in the arm by a dagger believed to be dipped in poison. Myth would have it that Eleanor saved her husband’s life by sucking the poison from the wound, though this is now believed to be apocryphal. What is certain is that during their time on the crusade Eleanor gave birth to her sixth child Joan, who became known as Joan of Acre after her place of birth.

In September 1272 the couple arrived in Sicily to be given news of Henry’s death. One may have expected the royal couple to have hastened back to England but, given the political stability that now existed in the country, they were in no rush to return, stopping off in Gascony to put down a rebellion! They finally arrived in England on 2nd August 1274, with Edward’s coronation being held seventeen days later.

Land-owner, literature lover and fan of forks

With Eleanor now queen, the records of her life become more comprehensive and illuminating. She continue to support and advise Edward in matters of state, and to acquire estates and landholdings – including Leeds Castle in Kent which became a favourite. She also gives birth to a further seven children, the last of whom, Edward, would go on to succeed his father to the throne. As a patron of literature she sponsored the production of illuminated manuscripts through her own scriptorium – the only one in northern Europe at the time. She is also credited with introducing the use of forks to the Court!

In 1286 the couple travelled to Gascony for what was planned to be a one-year stay, however they did not return to England until 1289. During Edward’s absence a state of lawlessness had arisen and Eleanor thought it essential to visit her estates. The starting point was Leeds Castle, followed by visits to estates in Suffolk and Norfolk. They then journeyed to Walsingham, home to the famous shrine, for what was probably an intercession for her worsening health. The couple then returned to London, spending their last Christmas together at Westminster.

At this point Eleanor must have been acutely aware of her declining health as she started to plan for the marriages of three of her children, Margaret, Joan, and Edward.

She intended to review her estates in the North when the couple embarked on their final journey in late July 1290. Progress was gradual and the cortege reached Harby on the border of Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire in November. Eleanor was now too unwell to travel back to London. She passed away on 28th November, with Edward as always, by her side. It is not known with any certainty what caused Eleanor’s death; one view is that she suffered from the effects of an infection after contracting malaria in Gascony, another is that she was suffering from some form of congenital coronary disease.

The Eleanor Crosses

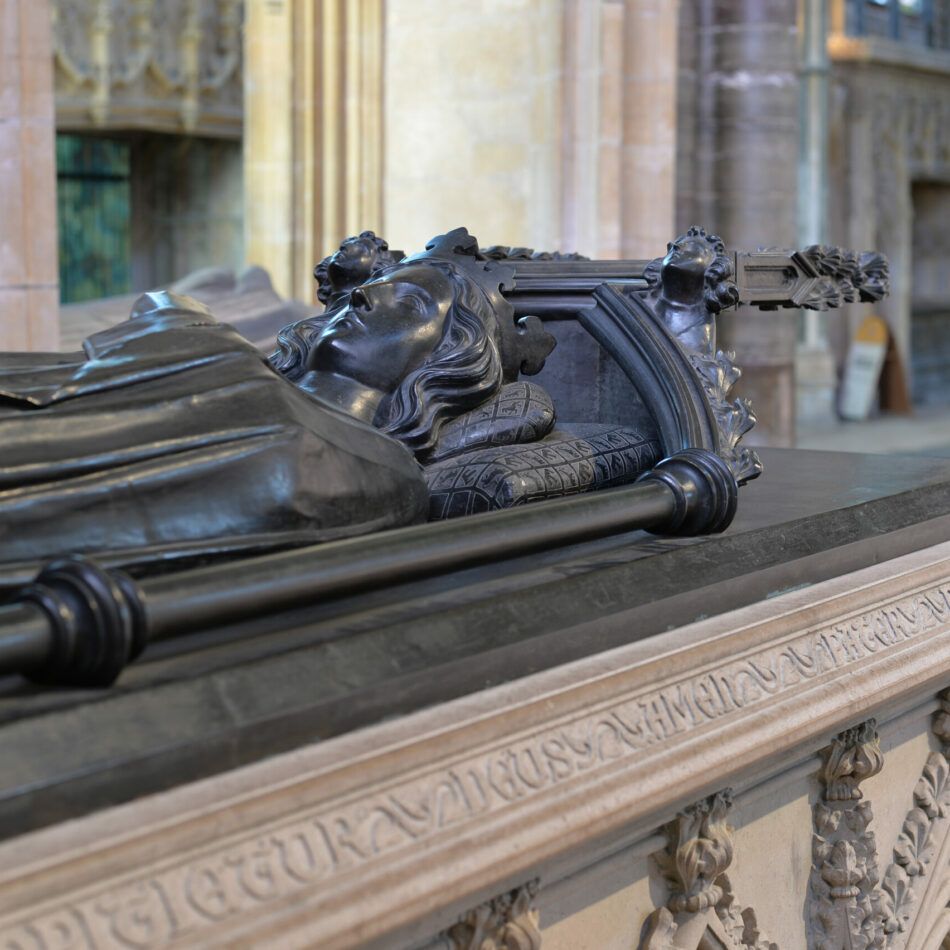

Eleanor’s body was taken to Lincoln where it was eviscerated and embalmed, probably by the Lincoln Dominicans. On 3rd December Eleanor’s viscera (minus the heart which was later interred at Blackfriars Church, London) were buried in the cathedral and on the next day the funeral cortege left Lincoln on its journey to Westminster Abbey, where she was buried in a magnificent tomb, a replica of which now stands in the Angel Choir at Lincoln.

The stopping places for the cortege were later marked, on Edward’s instructions, by twelve stone crosses. Built between 1291 and 1295, most of the crosses were subsequently destroyed or badly damaged by Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War of 1642-1651, but those at Geddington and Hardingstone have survived largely intact.

The crosses were a statement of Edward’s grief at his loss – a sentiment reflected in a letter to Abbot Cluny in France when he wrote of she “whom in life we dearly cherished and whom in death we cannot cease to love.”